Bach

Mülhausen. Actus Tragicus BWV 106 i la qüestió de la fe a l’hora d’escoltar Bach.

1723: BWV 76, 25, 105, 46, 109, 70

1724: BWV 20, 101, 38, 36, 91, 121, 65, 127, 6, 103, 74, 68, 176, Passió segons Sant Joan BWV 245

Música i text, BWV 77. Teologia o música. BWV 78, 95. Motets 229 i 225

Bach a Leipzig, Darrer any 668a, Visió final

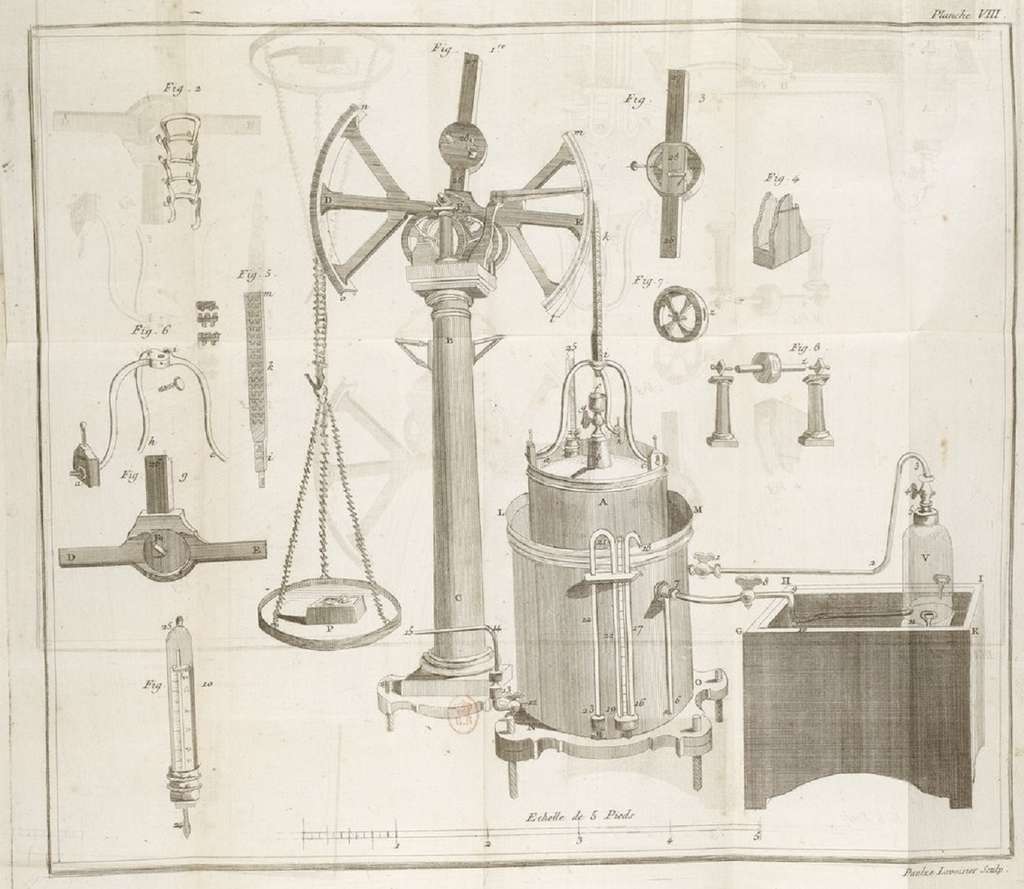

[Gardiner explica que la manera de rebre la música de Bach no era amb la devoció dels concerts d’avui. La cantata estava pensada per ser interpretada just abans del sermó dins d’un ofici religiós llarg, i la idea era preparar els fidels per escoltar-lo. Però coincidia que la gent important arribava just per fer-se veure al moment del sermó, irrompia i saludava els coneguts mentre s’asseien. Pintures d’Emanuel de Witte i Hendrick van Vliet, mostren gossos fent pipi a les parets blanques de la Oude Kerk a Delft. S’assajava a correcuita durant la setmana. Els textos eren anònims en general, amb una teologia sinistra que veu el món com “a hospital peopled by sick souls whose sins fester like suppurating boils and yellow excrement” Veure sinó la cantata BWV 199.]

Mülhausen

- BWV106. Many of his later works, including the two great Passion settings, deal with the same subject as a dichotomy between a world of tribulation and the hope of redemption – quite standard in the religion of the day. But none does so more poignantly or serenely than the Actus tragicus.u This extraordinary music, composed at such a young age, is never saccharine, self-indulgent or morbid; on the contrary, though deeply serious, it is consoling and full of optimism. Unlike some of Bach’s busier contrapuntal inventions, it has good ‘surface’ attraction, no doubt as a result of its unusually soft-toned instrumentation: just two recorders, an organ and a pair of violas da gamba. With this restricted palette Bach manages to create miracles: the opening sonatina comprises twenty of the most heart-rending bars in all of his works. From the yearning dissonance given to the two gambas, to the ravishing way the recorders entwine and exchange adjacent notes, slipping in and out of unison, we are being offered music to combat grief. Jean-Philippe Rameau once implored one of his pupils: Mon ami, faites-moi pleurer! 24 Listening to Bach’s sonatina, we are shown what Rameau meant and are moved. The whole work lasts less than twenty minutes and flows seamlessly through several switches of mood and metre. As often in the best music, there is a brilliant use of silence. After inserting a sequence of pleas for release from this world in which the soprano sings ‘Yes, come, Lord Jesus!’ several times over, Bach ensures that all the other voices and instruments drop out one by one, leaving her unsupported voice to trail away in a fragile arabesque. Then he notates a blank bar with a pause over it. This active, mystical silence turns out to be the exact midpoint of the work.

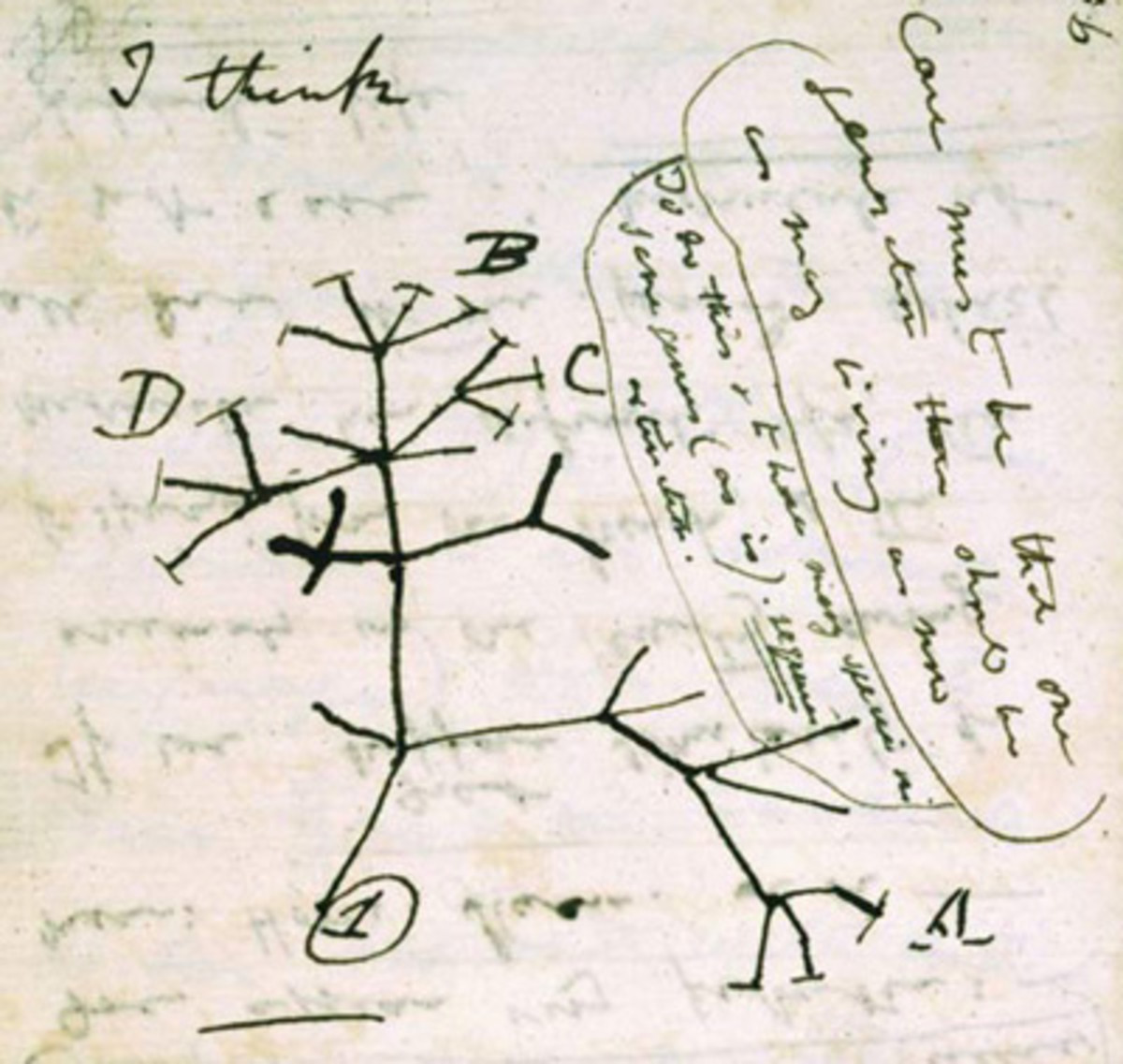

The Actus tragicus also raises the delicate issue of religious belief – whether the partial or total presence (or absence) in the listener can influence receptivity to music. It would be invidious to insist that a person needs to hold Christian beliefs in order to appreciate Bach’s church music. Yet it is certainly the case that without some familiarity with the religious ideas with which it is imbued one can miss so many nuances, even the way his later music can be seen to act as a critique of Christian theology.The problem is hardly new. In a letter to Erwin Rhode (1870) Friedrich Nietzsche wrote, ‘This week I heard the St Matthew Passion three times and each time I had the same feeling of immeasurable admiration. One who has completely forgotten Christianity truly hears it here as Gospel.’28 Yet in 1878 he was to complain, ‘In Bach there is too much crude Christianity, crude Germanism, crude scholasticism … At the threshold of modern European music … he is always looking back towards the Middle Ages.’ Nietzsche points to the conflict some people experience in relation to Bach’s church music: put off by the harshness of some of the language, they are nonetheless in thrall to the music and the way it carries the conviction of his faith.In the process of reconciling these opposite responses one can empathise with William James on the subject of religion in general – using ‘every fibre of his intellectual energy to defend and justify freedom of the will’ and, in his phrase, ‘the right to believe’. Religion, he recognised, ‘like love, like wrath, like hope, ambition, jealousy, like every other instinctive eagerness and impulse … adds to life an enchantment which is not rationally or logically deducible from anything else’.29 At the same time it can embrace the torments of the ‘sick soul’ finding consolation in conversion, as seen in Augustine, Luther and Tolstoy, and the fascination of the divided self, as seen in John Bunyan – and indeed Bach.30 With him, music inspires a religious sensibility that is very common but not necessarily tied to a specific dogma. Just as there are many non-religious aficionados of Bach’s church music, so there are atheists among Bach-loving professional musicians. One of the most widely revered figures among contemporary European composers, György Kurtág, recently confessed, ‘Consciously, I am certainly an atheist, but I do not say it out loud, because if I look at Bach, I cannot be an atheist. Then I have to accept the way he believed. His music never stops praying. And how can I get closer if I look at him from the outside? I do not believe in the Gospels in a literal fashion, but a Bach fugue has the Crucifixion in it – as the nails are being driven in. In music, I am always looking for the hammering of the nails … That is a dual vision. My brain rejects it all. But my brain isn’t worth much.

Comença el cicle amb el primer diumenge després de Trinitat.

Primer cicle 1723:

- BWV75

- BWV76 (salm 19, The idea of the entire cosmos celebrating God’s rich creation was a gift to a composer of Bach’s conceptual ability. It allowed him to contemplate and expound the meaning of infinity, a concept that was largely sidestepped throughout the Middle Ages, of the cosmos being aware of itself, of how ‘nature and grace speak to all of mankind’, showing us how as humans we can marvel about our own ability to do so. Bach’s vision is reflected in his choice of instruments: regal trumpets in Part I to symbolize God’s glory; a viola da gamba, that ancient instrument he uses at moments of the most intense feeling, to underline the human potential for faith and love in Part II. Treating the poverty/riches antithesis would have been enough for most other composers. Instead Bach and his unknown librettist (could it have been Gottfried Lange, the poet–burgomaster, who was acting almost as his patron in these early years of his cantorate?) looked for ways to enrich the connective tissue. In his First Epistle, John focuses on the meaning of love for humanity – conveyed by Bach in a majestic aria for bass and trumpet (BWV 75/xii) – and then, the following week, on brotherly love (die brüderliche Treue) as the basis of worldly life, the means by which mankind gives honour to God (BWV 76/xi).

- BWV25. ‘The whole world is but a hospital’ declares the tenor at one point in BWV 25, Es ist nichts Gesundes an meinem Leibe: Adam’s Fall has ‘defiled us all and infected us with leprous sin’.k Sickness, raging fever, leprous boils and the ‘odious stench’ of sin are described in detail in the text of this cantata, making no concession to the listener’s delicacy of feeling or potential queasiness. Although the unknown librettist builds to an impassioned appeal to Christ as the ‘healer and helper of all’ to cure and show mercy, it is Bach’s music that completes the spiritual journey for us. As listeners we sense this happening, but it is difficult to say how he affects a change in our perception of what the words are saying. Take the opening chorus with its gloomy description of a sin-ridden world: ‘there is no soundness in my flesh because of Thine anger; neither is there any rest in my bones, because of my sin’ (Psalm 38:3). Having set things in motion to underscore the words by every corroborative means he could devise (two-voiced canons, sighing motifs and unstable harmonies modulating downwards), Bach had, one might imagine, exhausted his expressive arsenal, but not so. In the fifteenth bar he brings in a separate ‘choir’ made up of three recorders, a cornett and three trombones to intone the familiar ‘Passion Chorale’,l one phrase at a time. Bach has added an independent commentary of his own which gradually works its magic, instilling the idea of hope and consolation. Here he reaches out to his listeners, his music serving as a kind of spiritual blood transfusion, in which the critical agency in the healing process emanates from the music, not the words.

- BWV 105 i 46 reflecteixen la nova manera de compondre cantates. With summer giving way to autumn, the focus of the appointed texts for each Sunday is on the hazards of living in society – with warnings against false prophets and hypocrites and how to live righteously in a sin-affected world./ Having already acquired the knack of how to vivify a doctrinal message and, when appropriate, of delivering it with a hard dramatic kick, he is now exploring ways of how and when to balance it with music of an emollient tenderness, humouring and softening the severity of his texts while in no way blunting their impact. Time and again one senses Bach’s exceptional level of engagement with the words, his music going far beyond literal mimesis or the codified use of conventional figures and symbols. / Autumn passes to winter the themes of the week become steadily grimmer as the faithful are urged to reject the world, its lures and snares, and to focus on eventual union with God – or risk the horror of permanent exclusion. From week to week this dichotomy appears to grow harsher, with the stress on sin and guilt deepening as the weather worsens.

- BWV 109, BWV 70. To convey the inner conflict between belief and doubt in BWV 109, Ich glaube, lieber Herr, hilf meinem Unglauben!, we find him assigning two opposing ‘voices’, sung by the same singer, one marked forte, the other piano. / For his final cantata of the Trinity season, BWV 70a, Wachet! betet! betet! wachet!, with its play on words, Bach increases the voltage.

- Nadal, Epifania. For Epiphany + 4, what must count as Bach’s most ‘operatic’ cantata bursts into life: BWV 81, Jesus schläft, was soll ich hoffen? Here he gives his listeners a foretaste of the enthralling music they could expect when his imagination was torched by a particularly dramatic incident. Based on Matthew’s description of Jesus’ calming a violent storm on the sea of Galilee that threatens to capsize the ship in which he and his disciples are sailing, it makes a sea voyage into a metaphor for the Christian life. It begins with Jesus asleep on board ship, the backdrop to an eerie meditation on the terrors of abandonment./old-fashioned recorders added to the string band for an aria for alto, the voice Bach regularly uses for expressions of contrition, fear and lamenting. Here he challenges the singer to a serious technical (and symbolic) test of endurance: to hold a low B without quavering for ten slow beats and then to negotiate a series of angular leaps and twists (through diminished and augmented intervals) to evoke the gaping abyss of approaching death./ Life without Jesus – his somnolent silence lasts all the way through the first three numbers – causes his disciples, and of course Christians ever since, acute anguish and a sense of alienation that rises to the surface in the tenor recitative with its dislocated, dissonant harmonies. In the background of the night we hear the words of Psalm 13 – ‘How long wilt thou forget me, O Lord, for ever? How long wilt thou hide thy face from me?’ – and the image of the guiding star precious to all mariners and to the magi. Suddenly the storm bursts. A continuous spume of violent demisemiquavers in the first violins is set against an unabated thudding in the other instruments. It reaches a succession of ear-splitting cracks on diminished seventh chords conveying the rage of ‘Belial’s waters’ beating against the tiny vessel. It is similar to one of Handel’s powerful ‘rage’ arias, demanding an equivalent virtuosity of rapid passagework by both tenor and violins, but imbued with vastly more harmonic tension – what Paradise Lost might sound like if set as an opera. Three times Bach halts the momentum mid-storm for two-bar ‘close-ups’ of the storm-tossed mariner. Though it feels intensely real, the tempest is also an emblem of the godless forces that threaten to engulf the lone Christian as he stands up to his tormentors. It is extraordinary what a vivid scena Bach has created from its beginning in a simple allegro in G major for strings alone. Jesus, now awake (as if he could possibly have slept through all the mayhem), rebukes his disciples for their lack of faith. In an arioso with straightforward continuo accompaniment, almost a two-part invention, the bass soloist assumes the role of vox Christi. After the colourful drama of the preceding scena the very sparseness and deliberate repetitiveness of the music is striking. One wonders whether there is a pinch of dramatic realism here, of yawn-induced rebuke (the repetition of warum?) or even of mild satire – one of those occasions when Bach may be poking fun at one of his Leipzig theological task-masters. There follows a second seascape, almost as remarkable as the earlier tempest, this time as an aria for bass, two oboes d’amore and strings. The strings are locked in octaves, a symbol of order to show that even the pull of the tides, the undertow and the waves welling up can be checked just as they are about to break by Jesus’ commands Schweig! Schweig! (‘Be silent!’) and Verstumme! (‘Be still!’).

- BWV 67. The first in this sequence, BWV 67, Halt im Gedächtnis, is especially impressive: the music vibrates with a pulsating rhythmic energy and a wealth of invention. Bach’s task here is to depict the perplexed and vacillating feelings of the disciples, their hopes dashed after the Crucifixion. He conveys the palpable tension between Thomas’s doubts and the need within the group to keep faith (the corno blasts this out as a sustained single note in the opening chorus, an injunction to ‘hold’ Jesus in remembrance). / Three times their anxiety is quelled by Jesus’ beatific utterance Friede sei mit euch (‘Peace be unto you’). At its fourth and final appearance the strings abandon their storm-rousing and symbolically melt into the woodwind’s lulling rhythms. In this way the scene ends peacefully, the concluding chorale acknowledging the Prince of Peace as ‘a strong helper in need, in life and in death’.

Segon cicle 1724: Bach’s decision to ground his Second Leipzig Cycle on Lutheran chorales was by no means arbitrary: it was a key difference between this and the first cycle, in which a scriptural dictum (or Spruch) had provided the opening to most of his pieces. / At all events, to plan a full cycle grounded on hallowed and iconic Lutheran hymns was one of Bach’s most courageous decisions as a composer – one that he sustained for the next nine and a half months with extraordinary consistency. For the next year Bach stuck limpet-like to these hymns: a total of fifty-two new cantatas used them as their starting-point and, once elaborated, gave them fresh currency.

- BWV 20. That much is clear from the outset of his first cantata, BWV 20, O Ewigkeit, du Donnerwort. It is an astonishing piece, one that sets the tone for the whole cycle and sums up so many of the original features we will encounter – a new range of expression, the use of operatic technique to enliven the doctrinal message and wild contrasts of mood./ Where the previous year’s vision was of a faith-propelled anticipation of eternity in BWV 21, fear, rather than comfort, is now the subtext of BWV 20 – the chilling prospect of an eternity of torture and pain. / Powerful cross-accents and a huge upward sweep for the basses on Traurigkeit (‘grief’) characterise the double fugue. Abruptly the orchestra screeches to a halt on a diminished seventh. Only a bold dramatist would risk stopping the forward momentum to convey trepidation – personal and petrifying – and Bach had good reason to be proud of this. (Any late-coming worshippers entering at that point would have been frozen to the spot, their neighbourly greetings silenced.) Out of the ensuing silence, terse and angular fragments are tossed from oboes to strings and back again in anticipation of the choir’s resumption. / Climbing back into his pulpit, the bass delivers the harrowing prospect of ‘a thousand million years with all the demons’. Then, as he moves from recitative into aria, he abruptly changes tack and tone. We appear to have been shunted into the world of opera buffa, or, rather, of ducks – three of them (all oboes) and a bassoon. /

Perhaps Bach could see no further way to develop the theme of eternity before offering a speck of hope to the Christian soul now thoroughly battered and bruised. He reminds us that the solution to life’s problems is childlike in its simplicity. / Bach’s depiction of hell is far richer and more polychromatic than that of any other composer before Mozart and Berlioz. So much of his richness comes from the dissonance that runs from the smallest to the largest./ A logical choice for his theme would have been the call to the lost sheep to wake up and throw off the sleep of sin (Ephesians 5:14), the subject of the electrifying bass aria with trumpet and strings which opens Part 2 – Bach’s answer, as it were, to Handel’s ‘The trumpet shall sound’ from Messiah – a taxing piece for both singer and trumpeter, requiring dramatic delivery and technical control. As if that were not enough, the alto soloist now blasts off in a tirade against the carnal world, much along the lines of an Oxford Street sandwich-board-wearer: ‘Repent before it’s too late: the end is nigh.’w And with this message comes a twist calculated to bring the listener up short: ‘Consider … it could be this very night that the coffin is brought to your door!’ It is not very often that Bach resorts to lurid pictorialism of the Hieronymus Bosch kind; yet, in the ensuing duet delivered to the errant pilgrim as though by Bunyanesque angels (alto and tenor), he treats us to a ghoulish cameo of ‘howling and chattering teeth’, of the ominous approach of the hand-drawn hearse as it clatters across the cobbled street. Successions of first inversion chords over a disjointed bass line in quavers with parallel thirds and sixths in the voice parts give way first to imitative and answering phrases, then to an anguished chromaticism evoking the bubbling stream and the drop of water denied to the parched rich man. The voices join for a final flourish. We hear the gurgling of the forbidden water and the continuo playing a last furtive snatch of the ritornello. Then, dissolve … fade out … silence. Extraordinary.

- BWV 101, Nimm von uns, Herr, du treuer Gott. Ten Commandments (Dies sind die heil’gen zehn Gebot). / Over the final tonic pedal Bach engineers a disturbing intensification of harmony and vocal expression for the words für Seuchen, Feur und großem Leid (‘contagion, fire and grievous pain’). Here we sense Bach working his chosen motifs as hard as he possibly can, a trait we associate more readily with Beethoven./There is a single moment midway, enough to strike horror in the listener, when Bach makes an abrupt Mahlerian swerve from E minor to C minor on the word Warum [willst du so zornig sein?]. Not even Purcell, with his penchant for a calculated spot-lit dissonance, was capable of matching this when setting the same words in his anthem ‘Lord, how long wilt Thou be angry?’ Sudden juxtapositions of sacred text and personal commentary are a potent new dialectical weapon in Bach’s expressive arsenal. / … whole fresh layer of minutely differentiated articulation and dynamic markings now appeared to enable him and future musicians to realise the precise nuances present in his imagination. Deciding to write out a new flute part for the musical highpoint of the cantata, the soprano-alto duet, and as economical as ever with manuscript paper, he wrote it on the back of the cornet part.

- BWV38 The theme of the hidden granting of faith returns later in the season in BWV 38, Aus tiefer Not schrei ich zu dir, for Trinity +21, based on Luther’s paraphrase of Psalm 130: he describes the cry of a ‘truly penitent heart that is most deeply moved in its distress … We are all in deep and great misery, but we do not feel our condition. Crying is nothing but a strong and earnest longing for God’s grace, which does not arise in a person unless he sees in what depth he is lying.’15 Bach would have known that Luther’s hymn was linked to a time-honoured Phrygian tune, one so perfectly suited to archaic treatment in motet-style that it is hard to imagine him setting it in any other way. /Once again he doubles each of the four voices with a trombone – a technique one might associate more readily with Schütz or even with Bruckner than with Bach. Besides their unique burnished sonority, these noble instruments bring a sense of ritual and solemnity to the overall mood. Bach seems intent on pushing the frontiers of this movement almost out of stylistic reach through the abrupt chromatic twists he gives to its modal tune. / All three of the cantata’s final movements are equally stern and uncompromising. Bach marks the recitative for soprano a battuta – unusually, to be sung in strict tempo – while the continuo thunders out the old tune as if daring the believer to give in to doubts in a magnificent reversal of usual practice, the singer’s weakened faith scarcely having time to express its frailty. As with his cantata for this Sunday from the previous year (BWV 109), he delays the provision and granting of help until the last possible moment. With all the voices given full orchestral doubling (including those four trombones), this chorale is not simply impressive, it is even intimidating in its Lutheran zeal – especially its final Phrygian cadence, with the bass trombone plummeting to bottom E.

- BWV26 The instrumental ritornello to the opening chorale fantasia of BWV 26, Ach wie flüchtig, ach wie nichtig, is a stupendous musical confectionery illustrating the brevity of human life and the futility of earthly hopes. / Fleet-footed scales, crossing and re-crossing, joining and dividing, create a mood of phantasmal vapour – a brilliant elaboration of an idea that first came to him ten years earlier in Weimar./ There does seem to be a proto-Romantic Gestalt to the way Bach set it as an aria for tenor, flute, violin and continuo: each musician is constantly required to change functions – to respond, imitate, echo or double one another – while contributing to the inexorable forward motion of the tumbling torrent and a brief episode of falling raindrops. Human life first as mist and spray, then as a mountain torrent; next, Bach turns to the inevitability of beauty’s withering like a flower and the moment when man succumbs to earthly pleasures and ‘all things shatter and collapse in ruin.

- BWV 91 Christmas Day itself began with BWV 91, Gelobet seist du, Jesu Christ, Bach’s majestic setting of Luther’s hymn, whose opening ritornello has the special sense of expectation that is the hallmark of Bach in Christmas mode: fanfares for the horns and running G major scales in the oboes that suggest the dancing of angels. In the unselfconscious abandon of his setting of das ist wahr (‘this is true’) and the syncopated Kyrie eleis! (reminiscent of a similar word-setting in the Zwiegesänge of Michael Praetorius), Bach’s seventeenth-century roots are exposed; and this mood persists in the soprano recitative interwoven with the second verse of the hymn and in the festive tenor aria set for three oboes swinging along in genial accompaniment. / When Bach came to re-work this cantata during the 1730s, in order to illustrate the human aspiration to sing (and, by implication, dance) like the angels, he added lilting syncopations to the vocal lines that clash with the violins’ dotted figure. / The polarity between them is reinforced by means of upward modulations, once in sharps (as if to symbolise man’s angel-directed aspirations), once in flats (as if to represent Jesus’ humanity). The music brings to mind the vivid imagery of Botticelli’s dancing angels or Filippino Lippi’s angelic band in full cry on the walls of the Carafa Chapel in Santa Maria sopra Minerva in Rome. / He may have been inspired by the vision of St John Chrysostom (c. 347–407), which he surely knew – those ‘thousands of Archangels and ten thousands of Angels … six-winged, full of eyes, and soar aloft on their wings, singing, crying, shouting, and saying Agios! Agios! Agios! Kyrie Sabaoth! Holy, Holy, Holy, Lord God of Hosts!

- BWV 121. Bach adopts a wholly different strategy for its sequel the next day. More than in any other cantata you sense a primitive root, an early Christian origin for the Marian text of BWV 121, Christum wir sollen loben schon, one of the oldest-feeling of all Bach’s cantatas. Luther had appropriated and translated a famous fifth-century Latin hymn, ‘A solis ortus cardine’ (‘From the rising of the sun’), used for Lauds during the Christmas season, and Bach sets its opening verse in motet style, the voices doubled by a cornett and three trombones in addition to the usual oboes and strings. There is something mystical about this tune, not least in the way it seems to start in the Dorian mode and end in the Phrygian (or, in the language of diatonic harmony, on the dominant of the dominant). Replacing the portrayals of dancing seraphim are images of those angular, earnest faces that fifteenth-century Flemish painters use to depict the shepherds gazing into the manger-stall at the reinen Magd Marien Sohn (‘little son born of a spotless maid’). The archaic feel of the opening chorus seems perfectly attuned to the mystery of the Incarnation. Unequivocally modern, however, is the startling enharmonic progression – a symbolic ‘transformation’ no less – at the end of the alto recitative (No. 3) describing the miracle of the virgin birth. This is the tonal pivot of the entire work and, appropriately, it occurs on the word kehren (‘to turn or reverse direction’); with wundervoller Art (Bach’s play on words is his cue for a ‘wondrous’ tritonal shift) God descends and takes on human form, symbolically represented by the last-minute swerve to C major. It is the perfect preparation for the bass aria (No. 4), where bold Italianate string writing and solid diatonic harmonies are used to describe how John the Baptist ‘leapt for joy in the womb when he recognised Jesus’.

- BWV 65. One of the crowning glories of Bach’s first Christmas season was BWV 65, Sie werden aus Saba alle kommen, for Epiphany 1724, and it is fascinating to observe him attaining the same peak the following year in BWV 123, Liebster Immanuel, Herzog der Frommen – but via a different route. One of the keys to this lies in the instrumentation. Where the atmosphere of the earlier work is oriental and pageant-like, the second opens with a graceful chorus in a little reminiscent of an Elizabethan dance, with paired transverse flutes, oboes and violins presented in alternation./ With their haunting sonority these ‘hunting oboes’ seem to belong to the world of Marco Polo – of caravans traversing the Silk Route – and it remains something of a mystery how a specialist wind-instrument-maker, Herr Johann Eichentopf of Leipzig, could have invented this magnificent modern tenor oboe with its curved tube and flared brass bell around 1722 unless he had heard one of these oriental prototypes played by visitors to one of Leipzig’s trade fairs. / Bach draws on a most opulent scoring for this entrancing triple-rhythm aria for tenor (No. 6). Pairs of recorders, violins, horns, and oboes da caccia operate independently and in consort, exchanging one-bar riffs in kaleidoscopic varieties of timbre.bb The quality of the arias in BWV 123 is more telling still: a tenor aria (No. 3), with two oboes d’amore, describes the ‘cross’s cruel journey’ to Calvary with heavy tread and almost unbearable pathos belying the words ‘[these] do not frighten me.’ Four bars in a quicker tempo to evoke ‘when the tempests rage’ dissolve in a tranquil return to the lente tempo as ‘Jesus sends me from heaven salvation and light.’ This is followed by what is surely one of the finest, but also loneliest, arias Bach ever composed, ‘Lass, o Welt, mich aus Verachtung’ (‘Leave me, O scornful world / To sadness and loneliness!’). The fragile vocal line, bleak in its isolation, is offset by the flute accompanying the bass singer like some consoling guardian angel trying to inspire him with purpose and resolve. Even the B section (‘Jesus … shall stay with me for all my days’) offers only a temporary reprieve because of the expected da capo. Here voice and instrument are intimately linked, but with the wordless flute left to complete what the singer cannot bring himself to utter. A year later Bach returned to this mood of Epiphany blues with a second hugely demanding bass aria, ‘Ächzen und erbärmlich Weinen’ from BWV 13, Meine Seufzer, meine Tränen, describing how ‘groaning and piteous weeping cannot ease sorrow’s sickness.’

- BWV 127, Herr Jesu Christ, wahr’ Mensch und Gott, occupies a crucial role, for Bach placed a ‘chorale Passion’ like a jewel at its centre, just as he had done the year before. There are features of BWV 127, a strikingly experimental cantata, that function in the same way. The first occurs in the elegiac chorale fantasia that opens the work: here Bach weaves together no fewer than three chorale tunes – an instrumental presentation of the Lutheran Agnus Dei with its clear reference to Christ’s Passion, a funeral lament by the French composer Claude Goudimel (1565), and finally several strains of a chorale melody we recognise as that of the Passion chorale, Herzlich tut mich verlangen, which will feature so prominently in the Matthew Passion. Next, it is noticeable that the following recitative for tenor links the individual’s thoughts of death to the path prepared by Jesus’ own patient journey towards his Crucifixion. / self-quotation unique in Bach’s church music: for the solo part for bass is identical with the four choral entries of the spectacular double chorus ‘Sind Blitze, sind Donner’, one of the highpoints of the Matthew Passion and rightly identified.

- BWV 6 The ‘Great Fifty Days’ from Easter to Whitsun were rooted in the Jewish tradition of marking the seven weeks plus one day between Passover (the Feast of Unleavened Bread) and Pentecost/Shavuot (the Feast of the Weeks, and also the Day of the Ceremony (Bikkurim) of First Fruits – harvest, in other words). They signalled the completion of Jesus’ work on earth, his last appearances to his disciples, his valedictory message to them to bolster their faith, and his promise to protect them through the coming of the Holy Spirit. It is thus a season of contrasts – of joy at Christ’s resurrection and reappearances, clouded by the prospect of his departure and the adversarial pressures of life in the temporal world. / This duality between a world deprived of Jesus’ light and physical presence and a world of increasing spiritual darkness is very palpable in Bach’s cantata for Easter Monday, BWV 6, Bleib bei uns, denn es will Abend werden. / Bach finds a way of ‘painting’ these two ideas by juxtaposing the curve of descent via trajectories of downward modulation with the injunction to remain steadfast – threading twenty-five Gs, then thirty-five Bs played in unison by violins and violas all through the surrounding dissonance.

- BWV 103 Ihr werdet weinen und heulen, takes its title. It seems a little strange, therefore, to find that it opens with a glittering fantasia for a concertante violin doubled on this occasion by another unusual instrument – a soprano recorder in D, known as a ‘sixth flute’.

- BWV 74 Whit Sunday might seem a strange day for a graphic depiction of hell. That, however, is the purpose of the alto aria ‘Nichts kann mich erretten’ from BWV 74, Wer mich liebet, der wird mein Wort halten, which makes demands of a solo violin at the opposite end of the expressive spectrum usually associated with Bach’s writing for that instrument. He seems determined to convey to his listeners with stark realism the image of hellish chains being rattled by Jesus in his struggle with worldly forces. Accordingly he sets up battle formations for his three oboes and strings, asking his violinist to execute fiendish bariolage, with the lowest arpeggiated note falling not on, but just after, the beat. The effect is both disjointed and invigorating. Soon the vocal line embarks on arpeggios that appear trapped within the vehement dialectic, as though it were trying to work itself free from the hellish shackles. At times this search for belief is plaintive, with cross-accented phrases reinforced by the oboe and solo violin against a menacing thud of repeated semiquavers. In the B section victory seems assured and the singer ‘laughs at Hell’s anger’ against colossal smashing chords by the winds and strings in triple and quadruple stops

- BWV 68 At this point Bach was near to completing his ambitious design for the twelve Sundays leading up to Trinity Sunday, based on biblical citations. His settings of John’s words are full of purpose, never more so than in the final chorus of BWV 68, Also hat Gott die Welt geliebt, when, in place of a chorale, he puts to his listeners the chilling choice between salvation and judgement in the present life: ‘He that believeth on him is not condemned: but he that believeth not is condemned already’ (John 3:18). Bach’s setting is as uncompromising as the text: a double fugue whose two subjects describe the alternatives, the voices doubled by his familiar alliance of archaic brass instruments, a cornett and three trombones.

- BWV 176. Trinity Sunday marks the last in the sequence of nine cantatas to texts by Christiane Mariane von Ziegler. The title of BWV 176, Es ist ein trotzig und verzagt Ding, translates as ‘There is something stubborn [or defiant or wilful] and yet fainthearted [or despondent or despairing] about the human heart.’ All the permutations of these adjectives apply to Bach’s setting, an arresting portrayal of the human condition – and might also reflect his own views, particularly as regards the intractable attitude of the Leipzig authorities.

- La passió segons sant Joan BWV 245

No opera overture of the first half of the eighteenth century that I know comes closer to anticipating the moods of those to Idomeneo or Don Giovanni than the opening of Bach’s John Passion; nor is there a better direct ancestor to Beethoven’s three preludes to Leonore. For pictorial vividness and tragic vision, the turbulent orchestral introduction is without parallel. Like a true overture, it beckons us into the drama – not in a theatre, but in a church or, nowadays, often in a concert hall. The tonality – G minor – is one that from Purcell to Mozart usually implies lamentation. The relentless tremulant pulsation generated by the reiterated bass line, the persistent sighing figure in the violas and the swirling motion in the violins so suggestive of turmoil, even of the physical surging of a crowd – all contribute to its unique pathos. Over this ferment, pairs of oboes and flutes locked in lyrical dialogue but with anguished dissonances enact a very different kind of physicality, one that can create a harrowing portrayal of nails being driven into bare flesh.

It is entirely possible that such a unique fusion of music, exegesis and drama might have perplexed its original biblically saturated listeners, just as much as it seems guaranteed to pass over the heads of an often biblically disabled modern audience, who do, nonetheless, still find it so gripping./ Bach had set himself the herculean task of composing (as far as conditions and time allowed) new music each week for all the festivals in the church year, his initial target (most likely) a minimum of three annual cantata cycles, each with a Passion setting as its climax. Accordingly, the John Passion was to become his first major ‘planet’ encircled by its co-orbital ‘moons’ – the cantatas he had fashioned so far in his first season. / was his largest-scale work to date, one comprising forty separate movements and lasting over one hundred minutes, greatly exceeding any liturgical needs or directives, and one of a small selection of works that would occupy his thoughts at intervals for the rest of his career. It is significant that for two last performances in the year of his death and one the year before, he reverted in all essentials to its original state.

They had had almost a year in which to become accustomed to a style of music which Bach himself later freely admitted to the authorities was ‘incomparably harder and more intricate’ than any other music performed at the time.

The da capo structure that Bach adopts is no mere formality or structured conceit, as so often in contemporary opera: it is a metaphor for the entire Passion story in miniature. In the A section we are shown Christ glorified as part of the Godhead (‘Glorify thou me with thine own self with the glory which I had with thee before the world was’, John 17:5). The B section then refers to his abasement and anticipates the way he is destined to lay down his life for mankind. Finally, the reprise of the A section serves to mark Christ’s return to his Father in glory and majesty (Jesus prayed earlier that his disciples ‘may behold my glory, which thou hast given me’, John 17:24).l

John’s account is stretched over three ‘acts’. Act I (John 18:1–27) opens with the arrest and interrogation of Jesus at dead of night in the Sanhedrin court and comes to a head with Peter’s denial. Act II (18: 28–40 to 19: 1–16) then deals with the Roman trial in seven scenes on a split stage: the Jewish clergy and the mob outside the Praetorium, Jesus within and Pilate hovering from one to the other. It culminates with the passing of the death sentence. In Act III (19:17–42) the action shifts to Golgotha for Jesus’ Crucifixion, death and burial. With a sermon to accommodate at some point, it looks at first glance as though Bach intends to replicate John’s tripartite structure by placing it at the end of John’s Act I – his Part I, closing with the crowing of the cock in a verse from Matthew (26:75) which he interpolates to voice Peter’s remorse and bitter weeping.

For years I was struck by the way Bach seems to show an instinctive feel for knowing exactly when to interrupt the narrative and slow the pace down, when to intercalate solo arias in order to attach personal relevance to the unravelling of events, and when to insert ‘public’ chorales in which his listeners could voice (or hear voiced) their collective response.

There were sound theological precedents for his scheme in the way Lutherans were instructed first to read their Bible, then to meditate on its meaning, and finally to pray – in that order.

Two features of the trenchant crowd choruses immediately stand out: the rising chromaticism of the four voice lines in canonic imitation, and a manic whirling figure – usually in the flutes, once in the first violins, several times in both – that attached itself to the ‘mob’ ever since they first sent a search party out to arrest Jesus in Part I. Readily identifiable, too, is an incipient dactylic figure (long-short-short) first associated with the ‘delivering up’ of Jesus to Pilate but soon to be used with obsessive insistence – first by the Evangelist to convey (harshly) the whip-lashing ordered by Pilate and then (tenderly) in the long tenor aria meditation on that scourging. This figure will soon become the motto of the two fanatical Kreuzige choruses; but in those its remorseless bellicosity is welded to grinding dissonance, the product of fugal entries that have sprung out of the original oboe/flute collisions we noted in the opening chorus. The ferocity and sheer nastiness of these outbursts is chilling, especially as it reflects on us all (not just on the Jews and Romans): in Luther and Bach’s view we are all simul iustus et peccator, both sinless and sinning, and therefore inescapably implicated in the mob frenzy and mindless brutality that saw an innocent man condemned to be crucified. Bach finds two very different but equally compelling strategies to round out this portrayal: a sarcastic triple rhythm piece for the Roman guard ordered to stage Jesus’ mock coronation (with another of those twirling-whirling figures in the woodwind suggestive of a grotesque game of Blind Man’s Buff); and a pompous swaggering fugue-subject – of the kind that Handel was soon to use in his English oratorios to characterise his Old Testament baddies. Bach uses it to capture the self-righteous laying down of the secular law by the High Priest and his cronies – a clear trap for Pilate. Painters from Giotto to Hans Fries and Pieter Bruegel the Elder had found ways of bringing a vernacular realism to biblical scenes and to faces contorted by hatred.

Next he points to the way each of the five turbae encompasses the full span of chords associated with the ‘ambit’ of each particular key in which they are set and finds here ‘a striking resemblance to the ancient idea of Christ as Creator-Logos binding all things together into a cosmic system, or systema’.

My experience is that in performance this chorale, despite the ravishing cadence that precedes it, as though to herald a reflection of great importance – of fate having been ordained – does not register either as the axis of the trial scene or as the hub of the entire Passion. That prerogative goes to the immensely impressive tenor aria ‘Erwäge’ (No. 20) – a meditation on Christ’s self-sacrifice in which, after the escalating savagery of the turbae, we are offered the metaphor of ‘the most beautiful rainbow’ reflecting the blood and water on Jesus’ flailed back as a reminder of the ancient covenant between God and Noah after the flood.bb Significantly Bach has placed it precisely to straddle the chapter division in John’s Gospel: immediately after the mob’s insistence on Barabbas as the prisoner to be released and culminating in the scourging of Jesus, one of two exceptional moments when Bach lays aside the Evangelist’s narration and gives theatrical specificity and horror to the gruesome reality of Jesus’ flogging by the Roman soldiers. This is one of the most shocking juxtapositions in the whole work: the Evangelist’s outraged and outrageous burst of loud melismatic ‘rage’, followed immediately by the dulcet tonality of the ensuing arioso (‘Betrachte, meine Seel’, No. 19). One moment we see Jesus’ back torn and blood-streaked by flogging, and the next we are encouraged to see it as something beautiful – as the sky in which the rainbow appears as a sign of divine grace – close to what J. G. Ballard had in mind, perhaps, when he refers to the ‘mysterious eroticism of wounds’.31 That Bach attached exceptional importance to this arioso and its succeeding aria is manifest both from their length (with the full da capo of the aria, the scene runs to more than eleven minutes) and its highly unusual scoring – for two violas d’amore and a continuo of (implied) lute, gamba and organ.cc Outwardly this looks like a high-risk strategy: to halt the gripping dramatic forward momentum of the Roman trial scene with its layers of political posturing, collusion and refutation. Yet Bach’s instinct was sound. This, the nadir of Jesus’ physical degradation, was precisely the moment to halt the motion and to reflect and meditate on its consequences for mankind – to balance an arioso and aria of moving subjectivity in response to the overall objectivity of John’s account. The listener is led by means of suggestive (and theologically loaded) metaphors – and still more by beguiling musical textures – to contemplate the lacerated body of Jesus, rather as Grünewald does in his Isenheim Altarpiece and Hans Holbein does in his Dead Christ in the Tomb, with ängstlichen Vergnügen (‘anxious pleasure’) in so far as it leads to a pained, uneasy gratitude.dd The eruptive force, sensuality and eroticism in Bach’s expression of religious sentiment in this central aria may have been another moment to unsettle the Orthodox clergy of Leipzig and turn them against him. In the arioso that follows we are presented with the equivalent of Dürer’s Passiontide woodcuts in which flowers, in this case Himmelschlüsselblumen (primroses or cowslips), bloom from the crown of thorns. Bach is ultra-precise in his choice of instruments here: a pair of violas d’amore, the most tender, consoling instruments in his locker, with their ‘sympathetic’ strings, contrasted with the lute (or, in a later version, harpsichord) to suggest the pricking of the thorns, and serving to point up the contrast by very obvious tonal means – a tritone leap in the voice from C to F on Schmerzen to instigate sharpened harmonies whose raised pitches and upward tritone give instantly recognisable musical equivalence to the forms, with the ensuing celestial relaxation going to the flat keys (G minor) for the blooming of the ‘key-to-heaven-flower’.

Most poignant of all is the way his last words – Es ist vollbracht – are carried through, imitated and transposed by the viola da gamba in the celebrated alto aria (No. 30). The use of this already old-fashioned instrument, with its highly individual and plangent sonority, an etiolated reflection of the human voice, is a calculated device – one that he had used only once previously, in his first cantata cycle (BWV 76) and was to use again in the Matthew Passion. Again, as in ‘Ach, mein Sinn’, Bach adopts the majestic gestural language of the High French style, but here with the opposite effect: where in Peter’s aria it was speeded up to convey extreme agitation, here it is dirge-like to explore the borderline between life and death.hh In the B section the gamba’s tone and melody disappear completely in the wild arpeggiation of the string band – a cameo image of Christ as the hero of Judah.

This aria is Bach’s strongest yet most balanced way of interpreting John’s account – as both a meditation on Christ’s suffering and as the victorious affirmation of his identity, the hidden God revealed through faith on the Cross.

There has to be an explanation why, in our secular age, listening to the John Passion seems to provide so uplifting an experience for so many people. I would suggest that the multilayered structure underpinning Bach’s Passion can be ‘felt’, if not immediately seen or heard, by the listener, in the same way that flying buttresses, invisible to the visitor when entering a Gothic church, are essential to the illusion of lightness, weightlessness and the impression of height.

Pasió segons Santr Mateu BWV 244

Bach’s autograph manuscript score of the Matthew Passion is a calligraphic miracle. /

Uniquely among his autographs, he uses red ink – but generally only for the Gospel words, which thus stand out from the rest like some medieval missal and from the brown-black sepia that was his norm.

… the case of ‘Erbarm es Gott!’ (No. 51) it is not just the hard edge to the rhythms which softens the bridge to the aria ‘Können Tränen’, but the extreme instability of the underlying harmony, made up of chains of seventh chords, which veers from sharps to flats, back to sharps and (just when you expect a final cadence in F minor) makes a last-minute enharmonic swerve to flats – to G minor. Picander’s arioso text refers to a ‘vision of such pain’ (der Anblick solchen Jammers).

… final reminder of this comes in the unexpected and almost excruciating dissonance Bach inserts over the very last chord: the melody instruments insist on B – the jarring leading tone – before eventually melting in a C minor cadence. Looking back at the conclusion of the Matthew Passion, one is struck by how the character of Jesus – a much more human figure than the one portrayed in the John Passion – is delineated powerfully and subtly, even when reduced, as in the whole of Part II, to three lapidary utterances: his final Eli, Eli, lama asabthani?

Bach knew perfectly well what opera was and seems to have decided quite early in life that it wasn’t for him. What most distinguishes his Passions from operas of the time is the way he does away with the convention of a fixed point of reference for the audience, rejecting the idea of a listener who surveys the development of the dramatic narrative more like a consumer – entertained, perhaps moved, ingesting spoon-fed images, but never a part of the action.

In his book The Death of Tragedy, George Steiner maintains there has been no specifically Christian mode of tragic drama even in the noontime of the faith. Christianity is an anti-tragic vision of the world … The Passion of Christ is an event of unutterable grief, but it is also a cipher through which is revealed the love of God for man … Being a threshold to the eternal, the death of a Christian hero can be an occasion for sorrow but not for tragedy … Real tragedy can occur only where the tormented soul believes that there is no time left for God’s forgiveness. ‘And now ’tis too late,’ says Faustus in the one play that comes nearest to resolving the inherent contradiction of Christian tragedy. But he is in error. It is never too late to repent, and Romantic melodrama is sound theology when it shows the soul being snatched back from the very verge of damnation.

Bach set in motion a new burgeoning of the genre, leading his listeners to confront their mortality and compelling them to witness things from which they would normally avert their eyes. Perhaps Steiner might concede that, in this regard, such is the mythic charge to Bach’s two great Passions, they could be considered the natural sequel to the spoken dramas of Racine and the English early-seventeenth-century writers, in so far as their themes resonate far beyond their temporal and liturgical borders, demonstrating that ‘context of belief and convention which the artist shares with his audience’. While there is enough documentary evidence to make it possible to reconstruct the original liturgical setting of Bach’s Passions,p we cannot of course recover the way people experienced them at the time. Since they have proved that they can survive treatments as different as the old massed-choir Victorian rituals (with their strong whiff of sanctimoniousness) and, at the other extreme, the minimalist nostrums of historically informed practice (HIP) – and still move people – we can be certain there is no one definitive way of interpreting them, whether in church, in concert halls or within the secular embrace of the theatre.

Sobre la relació entre música i text

People often complain that music is too ambiguous,’ wrote Mendelssohn in 1842. Everyone understands words, of course, but listeners do not know what they should think when they hear music. ‘With me,’ he said, ‘it is exactly the opposite, and not only with regard to an entire speech but also with individual words. These, too, seem to me so ambiguous, so vague, so easily misunderstood in comparison to genuine music, which fills the soul with a thousand things better than words. The thoughts which are expressed to me by music that I love are not too indefinite to be put into words, but on the contrary, too definite’. It is a startling statement, one many musicians would subscribe to but the very opposite of what some others would expect. The relation of music to language is as complex as that of language to thought. Language can elucidate, but it can also throttle sensibility in the process of its transmission. Music, on the other hand, when it is performed, allows that channel of transmitted thought and sensibility to flow with total freedom: it might not be very good at expressing our everyday mundane transactions, but the thoughts it does express are conveyed more clearly and fully than they would be by words. So what happens when you put the two together – as has happened from the beginning of time until the latest pop song? Any opera or cantata by necessity places text and its musical voicing in a symbiotic relationship, one that creates both opportunities and constraints for the composer.

It is, I hope, obvious from the previous three chapters that in Bach we are dealing with a composer who was never satisfied just to ‘set’ religious texts, whether cantatas, motets or Passions. Emanuel Bach told Forkel that his father ‘worked diligently, governing himself by the content of the text, without any strange misplacing of the words, and without elaborating on individual words at the expense of the sense of the whole, as a result of which ridiculous thoughts often appear, such as sometimes arouse the admiration of people who claim to be connoisseurs and are not’.2 That may well have been the impression Emanuel wanted to give – that his father did not normally flout eighteenth-century conventions of text-setting. But the truth is that Bach’s texted music is far from compliant: it opens the door to all-encompassing moods, which he evokes far more powerfully and eloquently than words could alone, particularly as his textures are so often multilayered and thus able to convey parallel, complementary and even contradictory Affekts.

As Laurence Dreyfus has shown, ‘he develops selective ideas from his texts that spark a dominating instrumental melody, but he also attaches signs, genres and styles foreign to the text that impose, by way of a kind of performance or execution of the text, an obscuring palimpsest on the poetry.’

Abstract music provides us with emotions purified of prescribed narratives and untethered from any pressing reality. / We get the sadness of loss without loss itself, the sensation of terror without any object of terror to which we have to respond, the luminescence of joy that melts away as we perceive it. / Bach was unwilling to have his orchestra reduced to the role of a docile accompanist simply laying down material in an opening ritornello that the singer would later develop and embellish.

Take BWV 169, Gott soll allein mein Herze haben, composed in October 1726, the last and most consistently beautiful of his cantatas for alto solo. Here we find Bach approaching a text in his most collusive manner, formulating a rondo motif to match the motto-like phrase extrapolated from the Sunday Gospel (Matthew 22:34–46): ‘God alone shall have my heart.’ This simple idea (the propositio in rhetorical terms) provides the basis for an overarching unity, while permitting an implied dialogue between this figure – the repeated self-offering to the love of God – and the gloss (confirmatio) given to it by poet and composer.

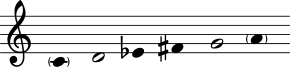

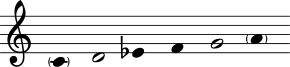

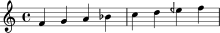

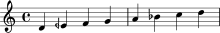

- BWV77 i l’ús de la trompeta

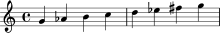

Coming as the climax of a series-within-a-cycle in his first Jahrgang, BWV 77, Du sollt Gott, deinen Herren, lieben, was an opportunity for Bach to give resounding, conclusive expression to the core doctrines of faith already adumbrated in the first four Sundays of the Trinity season. His aim is to demonstrate by means of every musical device available to him the centrality of the two ‘great’ commandments of the New Testament and how ‘on these two commandments hang all the law and the prophets’. This leads him to construct a huge chorale fantasia in which the chorus, preceded by the upper three string lines in imitation, spells out the New Testament statement. At this point he decides to encase the sung New Testament Commandments with a wordless presentation of the Lutheran chorale melody ‘Dies sind die heilgen zehn Gebot’ (‘These are the holy Ten Commandments’) to demonstrate how the entire Law is contained within the commandment to love. Calculating that he can count on his listeners to make the link between tune and text, he introduces it in canon, a potent symbol of the Law, between the tromba da tirarsi (slide trumpet) at the top of his ensemble and the continuo at its base – a graphic device to demonstrate that the Old Testament serves as the bedrock of the New, or rather that the entire Law is understood to frame, and be inseparable from, Jesus’ injunction to love God and one’s neighbour.

The strange thing is that whenever the chorale tune stops (in fact even before it gets going) the music reveals a searching, almost fragile quality – a quiet innocent introit without the usual eight-foot bass. Then comes a loud stentorian entry of the commandment theme (guaranteed to grab the attention of his congregation, you would think) and the choral voices thunder out ‘Thou shalt love the Lord thy God’ like so many evangelising sculptors chiselling the words out of the musical rock face. Suddenly a huge chasm in pitch, structure and dynamics opens up between the gentle interweaving of the imitative contrapuntal lines and the full, impressive weight of the double canon. Some find it helpful to hear this emphatic representation of height and depth as a spatial metaphor for the divine and human spheres – distant, yet interconnected. Beyond the obvious meshing of Old and New Testament commandments, the former strict in its canonic treatment, the latter freer and more ‘human’ in the working through of its vocal lines, is the symbolic separation of God’s control of the spheres of ‘above’ and ‘below’ (five statements of each, making ten in all). The music at this point is stupendous, the voices first in downward pursuit, then in upward, under the canopy of the trumpet’s final blast of the chorale tune. This is one of those breathtaking, monumental cantata openings that defies rational explanation. The end result is a potent mixture of modal and diatonic harmonies which leaves an unforgettable impression and propels one forwards to the world of Brahms’s German Requiem and beyond, to Messiaen’s Quartet for the End of Time – both overpowering works in which their very different music takes on Bach’s mantle of extending the biblical message through music to answer to the ultimate questions of fear and faith. What follows is a meditation on how ineffectual the believer’s will proves to be when attempting obedience to God’s commandments, and a foretaste of eternal life. Deceptive in its apparent simplicity and intimacy, an aria for alto is couched in the form of a sarabande, its weak phrase-beginnings and feminine cadences holding up a mirror to man’s proneness to fall short.

As a foil to the singer, Bach decides at this point to recall his principal trumpet – so assured and majestic in the opening chorus, but now single and unsupported except by continuo alone. His role here is to convey human imperfection (Unvollkommenheit) in the baldest terms. If he had set out to write an obbligato melody for the natural (or valveless) trumpet, Bach could hardly have devised more awkward intervals and more wildly unstable notes – recurrent C sharps and B flats, and occasional G sharps and E flats, which either do not exist on the instrument or else emerge painfully out of tune. In other words Bach is putting on display the shortcomings and frailty of mankind for all to hear and perhaps even to wince at.

To be the agent for illustrating the distinction between God (perfect) and man (flawed and fallible) is a tough ordeal for any musician unless you are a sad, white-faced clown, accustomed to playing your trumpet (badly) at the circus. But before jumping to the conclusion that Bach is being sadistic here, we should look beyond the surface of the music. Richard Taruskin claims that on occasion he ‘seems deliberately to engineer a bad-sounding performance by putting the apparent demands of the music beyond the reach of his performers and their equipment’.14 For that to be true, Bach would have had to allow for no remedial action to be available to his trumpeter using his large mouthpiece to ‘bend’ or ‘lip down’ (or ‘up’) the non-harmonic tones so as to make them slightly more acceptable, or to ask him to play the part on a tromba da tirarsi such as he often calls for in other contexts. The point is the effort Bach is concerned to illustrate as part of the music, and then, in blatant contrast, the ease with which, in the B section of the aria, he coasts through a ten-bar solo of ineffable beauty made up entirely of the diatonic tones of the natural trumpet without a single accidental: like some gleaming aircraft he emerges from a cloud bank into pure sunlight. Suddenly we are permitted a glorious glimpse of God’s realm, an augury of eternal life, in poignant juxtaposition to the believer’s sense of difficulty, incapacity, even, in executing God’s commandments unaided.i The device might be a bit drastic, but it is brilliantly effective. It requires the in-built unevenness of the natural trumpet to make its impact, which is simply lost when played on a modern chromatic valved trumpet. This is just a single example of the advantages historical instruments can bring to Bach performances. The techniques he uses in this cantata are extreme in their sophistication – in the first chorus by laying down the Law and in this aria by presenting the harsh dichotomy between God’s perfection and man’s efforts to imitate it. We are left wondering how an over-worked church musician, locked into numbing routines, could have come up with anything so inventive – and not as an isolated work but, as we saw in Chapter 9, as part of a coherent and highly impressive cantata cycle.

- Teologia? Música?

What can have spurred Bach to invent music of such density, vehemence and highly charged originality that it holds us spellbound? It is a question that has exercised scholars from the very beginning. Was it genuine religious fervour and the kind of single-minded dedication he exhibits on his title pages and in signing off each cantata with ‘SDG’ (‘To God alone the Glory’), or rather his innate sense of drama and an imagination instantly fired by strong verbal imagery?

However, we should not condone the tendency of theologically motivated commentators to treat the cantatas as doctrinal dissertations, as opposed to discrete musical compositions, any more than accept the glee with which aggressive atheists try to debunk any theological basis for Bach’s musical exegesis… the final analysis nothing can gainsay or diminish the overwhelming transformative force of Bach’s music, the very quality that makes his cantatas so appealing to Christians and non-believers alike. When we are presented with thoughts and feelings in music, with far more candour, clarity and depth than we would otherwise be capable of, this can bring a huge sense of relief. We might at first feel preached at or lectured, and resist.

- BWV78

BWV 78, Jesu, der du meine Seele, opens with an immense choral lament in G minor, a musical frieze on a par with the exordia of both his Passions for scale, intensity and power of expression. Bach casts it as a passacaglia on a chromatically descending ostinato with the ‘ground’ acting as a counter-balance to a hymn tune, and weaves all manner of contrapuntal lines around it. Where you might expect the three lower voices to provide a respectful accompaniment to the cantus firmus, Bach gives them unusual prominence, mediating between passacaglia and chorale, anticipating and interpreting the chorale text just as the preacher of a sermon might do. Indeed, such is the power of exegesis here, one questions whether Bach was once again inadvertently stealing the preacher’s thunder by the eloquence of his musical oratory. It is one of those opening cantata movements in which you hang on every beat of every bar in a concentrated, almost desperate attempt to dig out every last morsel of musical value from the notes as they come within earshot. Not in one’s wildest dreams, then, could one envisage a more abrupt sequel to this noble opening chorus than the delicious, almost frivolous duet that follows – ‘Wir eilen mit schwachen, doch emsigen Schritten’ (‘We hasten with weak but diligent steps’). Any straightforward reading of the text itself would not suggest a piece of such irreverence and frippery: you expect something dutiful, and instead you get a playful romp. With its moto perpetuo cello obbligato there are echoes of Purcell (‘Hark the echoing air’) and anticipations of Rossini. Bach’s wizardry encourages you to smile, tap your foot or nod in assent to the plea ‘May thy gracious countenance smile upon us.’

- Passió o asèpsia?

Passion in a Bach performance is a rare commodity in today’s climate of antiquarian purity and musicological correctness, but its absence jars with the miracle of Bach’s technical expertise, his mastery of structure, harmony and counterpoint, and his having imbued them with such vehemence, meaning and – exactly that – passion.

- Ocasions en que està menys inspirat

Though we are accustomed by now to Bach’s original, dramatic and sometimes wayward settings of words to music, we occasionally stumble across a movement that seems misconceived or indicative of a rare lapse of concentration. Take the melody of the soprano aria ‘Lebens Sonne, Licht der Sinnen’ from BWV 180, Schmücke dich, o liebe Seele, for instance. It starts out attractively, but after nineteen consecutive bars in which the singer continues to repeat the same words over and over again (‘Sun of life, light of the mind’), it risks becoming unbearable. The aria ‘Ich bin herrlich, ich bin schön’ from BWV 49, Ich geh und suche mit Verlangen, is not much better. It feels like an early draft of ‘I feel pretty, oh, so pretty’ from West Side Story; but, unlike Bernstein’s (and unlike, say, ‘Nur ein Wink’ from the Christmas Oratorio, where one welcomes each repetition), Bach’s tune does not have enough intrinsic interest beyond a certain surface attraction to warrant so many repetitions of the same words.

- Trompetes

One way Bach found to get around the rules and constraints of word-setting was to select an overall idea from the text that sparked the idea of a dominating instrumental sonority in his imagination. He came to know, for example, exactly how best to use the resources of the ceremonial trumpet-led orchestra and choir of his day to convey unbridled joy and majesty without knowing scientifically that the trumpet’s upper partials have a stimulating effect on the nervous system of the listener. /

One has only to think of the high trumpet writing in any of the choruses of the B minor Mass to realize what a potent and enthralling power this put at Bach’s disposal. / Take the opening of BWV 130, Herr Gott, dich loben alle wir – a song of praise and gratitude to God for creating the angelic host. Bach presents us with a tableau of the angels on parade: these are celestial military manoeuvres, some of them even danced, in preparation for combat. In the cantata’s centrepiece – a C major bass aria scored exceptionally for three trumpets …. Probably no composer before or since has written such a profusion of celestial music for mortals to sing and play – and no one could show off a trio of trumpets to such dazzling effect as Bach.

- Acceptar la incertesa

It is in this context that Keats’s famous formulation of negative capability has special pertinence – ‘when a man is capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason’. Keats’s rationalisation of the subjective allows joy and uncertainties to coexist, and provides an unintended denotation of the effect on the listener of Bach’s consoling music.

- BWV95

Bach’s imaginative capacity to convey through music and words the final stretch of the Christian pilgrimage reaches a peak in the second part of the opening chorus of BWV 95, Christus, der ist mein Leben. Here he depicts the struggle between the forces of life and death before the soul reaches its longed-for destination.

The only true aria in this cantata is one for a high-flying tenor – the mesmerising ‘Ach, schlage doch bald, selge Stunde’ (‘Ah, strike then soon, blessed hour’) – in which two oboes d’amore proceed in almost naked fourths, pausing every now and again to alight on a dissonance (the effect is similar to the way the echo of cracked bells hangs in the air) always accompanied by a persistent pizzicato of the Leichenglocken. But what exactly do they represent? Are they simply symbols introduced to resonate in his listeners’ minds, non-verbal means to trigger rhythmic patterns and sonorities in the aural imaginations of the bereaved?

- Motets 229 i 225

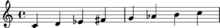

Equal fervour, but of a less militant, more sensuous kind, is to be found in the most intimate and touching of his double-choir motets, BWV 229, Komm, Jesu, komm. Bach’s explorations of the dialectical possibilities of eight voices deployed as two antiphonal choirs here, and in his Matthew Passion (see this page), goes many steps beyond the manipulation of spatially separate blocks of sound pioneered by the Venetian polychoralists and the rhetorically conceived dialogues of Gabrieli’s star pupil, Heinrich Schütz.

‘Hardly had the choir sung a few bars when Mozart sat up startled; a few measures more and he called out: “What is this?” And now his whole soul seemed to be in his ears. When the singing was finished he cried out, full of joy: “Now there is something one can learn from!” ’29 And why not? BWV 225, Singet dem Herrn, is by far the meatiest and most technically demanding of Bach’s double-choir motets, but that is not what dazzled Mozart in the Thomaskirche in Leipzig in April 1789, leading him to call for the parts, which he then ‘spread all around him – in both hands, on his knees, and on the chairs next to him – and, forgetting everything, did not get up again until he had looked through everything of Sebastian Bach’s that was there’. Nothing in Mozart’s previous experience of church music had prepared him for this – some of the most exhilarating dance-impregnated vocal music Bach ever wrote.

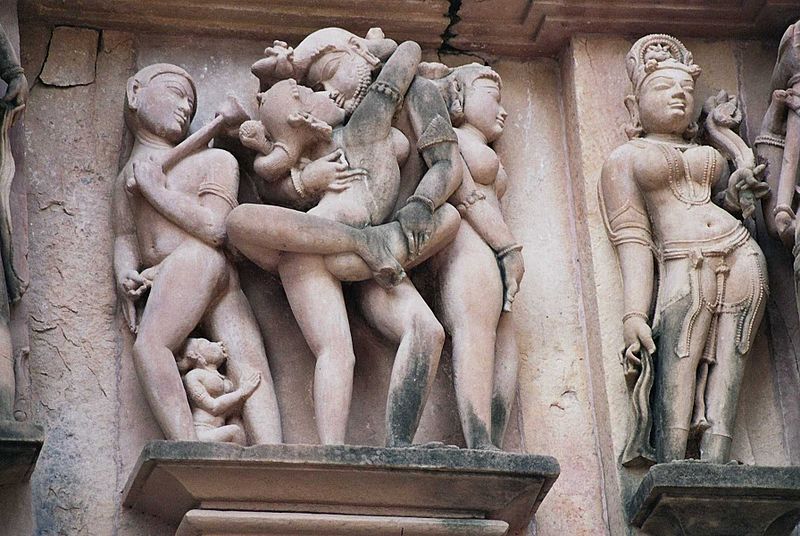

Passages such as these remind us that Bach’s is a Baroque version of medieval ‘danced religion’. Just as many African languages lack distinct words for music and dance, so these two were once considered inseparable in Christian worship, their pagan, Dionysian fusion legitimised by the early church Fathers.

To invoke ‘zest and delight of the spirit’, according to Clement of Alexandria (150–216), Christians were to ‘raise our heads and our hands to heaven and move our feet just at the end of the prayer – pedes excitamus’.30 He also instructed the faithful to ‘dance in a ring, together with the angels, around Him who is without beginning or end’ – an idea that, despite successive attempts of the church from the fourth to the sixteenth centuries to crack down on religious dancing in church, still held currency for Renaissance painters such as Botticelli and Filippino Lippi – and, I suggest, Bach, too, particularly in his Christmas music. At least Bach could claim the guarded backing of Luther, who, in accepting the legitimacy of ‘country customs’, said ‘so long as it’s done decently, I respect the rites and customs of weddings – and I dance anyway!’31 This is not very far from Émile Durkheim’s notion of ‘collective effervescence’ – the ritually induced passion or ecstasy that cements social bonds and which, he proposed, forms the ultimate basis of religion.v32 Suddenly we have a window on to those regular get-togethers of the Bach family – how their pious chorale-singing at the start of the day slipped into bibulous quodlibets at nightfall. Bach shared with his relatives a hedonistic vision of community based on the conviviality of human intercourse, one that in no sense clashed with his view of the seriousness of his calling as a musician or the funnelling of his creative talents to the greater glory of God. When Bach is in this mood, you sense that, for all its elegance, its dexterity and its complexity, his music has primitive, pagan roots. This is music to celebrate a festival, the turning-point of the year – life itself.

He brilliantly chooses to persist with the Singet motto that accompanied the imitative effusion of his initial prelude now as a funky, offbeat commentary to his four-part fugue. This pays high dividends in the build-up of this long movement, as one by one the voices of both choirs re-enter emphatically, this time in reverse order (B-T-A-S), while the rich ‘accompaniment’ is re-distributed among the fugally unoccupied voices. In his second pairing, the finale of the motet, Bach achieves a different type of transition from prelude to fugue by narrowing the focus: suddenly and without a break, eight voices converge and become four. Out of the hurly-burly the united basses of both choirs step forward in a passepied set to the words ‘Let everything that hath breath praise the Lord.’ This might sound straightforward enough, but in practice it is a challenge to achieve a seamless and fluent transition at this point of liftoff. It needs a readjustment of the singers’ ‘radar’ to pass from a full, dense eight-part polyphony in common time to fusion as a single line, one-in-a-bar, with spatially distanced voices now airborne, insubstantial and still dancing. Several episodes follow in quick succession – exposition, stretto, sequence, re-appearance of the subject in the super-tonic, sequence, stretto – each with expectations of an imminent conclusion. But Bach’s high-wire act still has 113 bars to run, and what promised to be a sprint to the line turns out to be a 1,500-metre race. As the singers move into the final straight, you sense the crowd’s excitement. Suddenly it’s no longer a flat race – there’s a big hurdle ahead, one to take the sopranos up to a top B before they can breast the finishing tape, using up the last Odem (‘breath’) of which they are capable.

Their popularity in our time goes a little way towards reversing the process of desocialisation that chased the choral dance first out of church and then from communal recreation of the kind we are told that the Bach family practised.33 (This was also a feature of my childhood, thanks to my parents’ no doubt unconscious re-creation of this pattern – intense sessions of a cappella singing, followed by physically liberating sessions of English country dancing based on John Playford’s The English Dancing Master (1651)). Through their extraordinary compression and complexity, Bach’s motets make colossal demands of performers, requiring exceptional virtuosity, stamina, and sensitivity to the abrupt changes of mood and texture as well as to the exact meaning of each word. Towards the end of his more than thirty years as music director of Berlin’s Singakademie in 1827, Carl Friedrich Zelter wrote to his friend Goethe, ‘Could I let you hear some happy day one of Sebastian Bach’s motets, you would feel yourself at the centre of the world, as a man like you ought to be. I hear the works for the many hundredth time, and am not finished with them yet, and never will be.’34 After knowing them for more than sixty years I feel exactly the same.

This music – playing it, participating in it, listening to it – conveys a strong sense of being in the present and screens out all else. The very act of performing such a Bach piece produces a type of realised eschatology, one which implies that ‘end times’ are in a sense already here.

Bach a Leipzig

Had he stayed in Cöthen (a Calvinist court) the project would have never got off the ground. Had he taken up the Halle offer in 1713, he might well have suffered the same fate as his eldest son, Wilhelm Friedemann, and become enmeshed in sectarian controversy there. In worldly Hamburg his energies, like those of his second son Emanuel later on, might gradually have been sapped by administrative duties and by the need to spread his music around the city’s churches even more thinly than in Leipzig. There, too, he would have become easy prey to the sardonic mockery of Johann Mattheson and other fashion-conscious advocates of the modern galant style. In beguiling, Catholic Dresden, with its richly endowed Capelle, he would not have been free to create and perform the succession of Lutheran church cantatas that he carried through.

It was the last time Luther could speak – vicariously but authoritatively – to his flock without widespread dissent. It had to be then, in that decade. Any later and the percolation of enlightened thought into middle Germany might have taken the edge off Bach’s creative zeal as the doors of fashion began to shut him out.

Now Bach the church cantata composer-performer starts to fade out of vision, and for the first time he opens doors to other composers’ works. Churchgoers no longer know, and perhaps do not even care, if he performs works by Telemann, Stölzel or his cousin Johann Ludwig Bach, and the text booklets on sale do not tell them what they are listening to. Compare this to the coffee-house concerts, where the public can see who is in charge at close quarters, even if as part of a throng of enthusiastic listeners they are scattered throughout different interconnected rooms. They are free to get up, move around, stand in the doorways, and comment on the music and the musicians in the style of a genteel academy of cognoscenti. Bach’s role in the mid and late 1730s embraces an increasingly secular world: urban Leipzig on the threshold of the Enlightenment.

- BWV668a, la darrera composició?

In acknowledging Bach’s humanity we begin to see how similar to us he was. If we forgo attempts to explain his genius (as a divine gift, or the result of genetics or nurture) we gain something richer – a sense of connection as well as a more nuanced, ‘grainier’ idea of how his music is put together and a clue as to why it should have such a deep emotional affect on us. Perhaps music gave Bach what real life in many respects could not: order and adventure, pleasure and satisfaction, a greater reliability than could be found in his everyday life. It was also there to complete those experiences that otherwise might have existed only in his imagination – part-compensation for those stimulating adventures denied to him but not to Handel, whose travels to Italy provided him with such a fertile source of inspiration. Bach found security in sticking to a regular structure, to proportion and numbers, and to the calendar. It was a trait that took a particular shape, gaining impetus, in his fifties through his almost obsessive absorption with genealogy and family trees.