The third book is about love and religious melancholy, or unhappiness related to love or religion.

The first section is about love in general, its definition in terms of desire , beauty as a cause, the possible objects of love according Augustine (God, the neighbor and the world); different kinds of love according the Aristotelian view on the soul, vegetative (in plants or stones), sensible love among beasts (each one for those of the same kind (sus sui, canis canis), and rational love , proper to men, angels and God.

There can be many kinds of love, women, the pleasures of fine foods, idols. Would it be possible that we loved virtues, wisdom, honesty, compassion? The observation of human nature turns Burton into a pessimistic, “ but this we cannot do “, man seems to have been born to hate, he says in an excellent piece of rhetoric: Where is charity ?

The second section deals with romantic love, or “heroical love”, a disease of the soul, according Avicenna and Arnau de Vilanova . It can affect the heart, liver, testicles, brain. (We have now research trying to find what happens in brains of people in love . )

What are the causes of love melancholy? How does it work? Visus, Colloquium, Convictus, Oscula, Tactus , sight, conversation, companionship, kissing, touch. We haven’t changed that much, it’s just that some modes of visus, colloquium and convictus can be carried out through facebook and twitter. We fall in love with “a little soft hand” or “ a small foot, a well proportioned leg ” or we fall under the effect of a sight. There is some ground in the many metaphors of sights that trespass ( Theory of the effect upon the soul by the eye ).

Love can benefit from artificial allurements , gifts, dance, voice, love potions. We can assert the existence of love from kissing, or when we can’t stop watching the beloved (as Frankie Vallie said Can’t take my eyes off you ). Burton avows that in those matters he is a novice and relies on readings and observation.

The cure. How can love melancholy be cured? While acknowledging his little experience, Burton tries to dissuade us from falling into the trap of love with a funny argument, suppose she is pretty, then she will be a fool, or anyway, old age will turn a venus into an Erynnia. Examine all parts of body and mind and some defect will be found. Finally, the advantages of being single: if you are young then match not yet , are you old, match not at all.

It doesn’t seem to take the issue very seriously because after having argued against love and marriage, he says that the last and best cure of Love-Melancholy,”is to let them have their Desires”, there is no joy like that of a good wife . An exercise in scepticism finds the same reasons for and against love.

_1. Res est? habes quae tucatur et augeat.–2. Non est? habes quae quaerat.–3. Secundae res sunt? felicitas duplicatur.–4. Adversae sunt? Consolatur, adsidet, onus participat ut tolerabile fiat.–5. Domi es? solitudinis taedium pellit.–6. Foras? Discendentem visu prosequitur, absentem desiderat, redeuntem laeta excipit.–7. Nihil jucundum absque societate? Nulla societas matrimonio suavior.–8. Vinculum conjugalis charitatis adamentinum.–9. Accrescit dulcis affinium turba, duplicatur numerus parentum, fratrum, sororum, nepotum.–10. Pulchra sis prole parens.–11. Lex Mosis sterilitatem matrimonii execratur, quanto amplius coelibatum?–12. Si natura poenam non effugit, ne voluntas quidem effugiet_.

Section there is about jealousy and infidelity.

Religious melancholy

In the introduction Burton warned against religion “in excess”; what ought to be love to God becomes superstition and idolatry, an infinite ocean of incredible madness and folly . We love the world too much, God too little . In the opposite, love divine “in defect” we find libertines or impious.

Where there is any religion, the devil will plant superstition. Burton offers a look at all known religions in the 17th century , Christians, Jews, Muslims; all of them, in their infinite variations, do what Machiavelli advised: use religion in order to control people. Priests manipulate believers to get privileges, superstitious pilgrimages are promoted to make advantage of ignorants. We do not know whether to laugh, with Democritus, or to weep, with Heraclitus. The Catholic Church, and their Pope are harshly criticized, for trading with relics, encouraging superstition to saints, miracles, apparitions, a whole “subterraneaous geography” just to frighten, and a lot of absurd theology (is it possible for God to be a humble bee? Can he create another God like itself?)

What is the cure for religious melancholy “in excess”? Tolerance , everyone can be saved if honest “because God is immense and infinite, and his nature cannot perfectly be known”, so different kinds of faith and religions can be accepted.

While the critics of religious melancholy “in excess” has been harsh, religious melancholy “in defect” is milder treated. It seems as if Burton formulates its own doubts: a possible pantheism, the determinism of stars (instead of astrology now we would speak of physics determinism), the problem of Evil , si not sit Deus, unde bona? si sit Deus, unde mala?

Despair

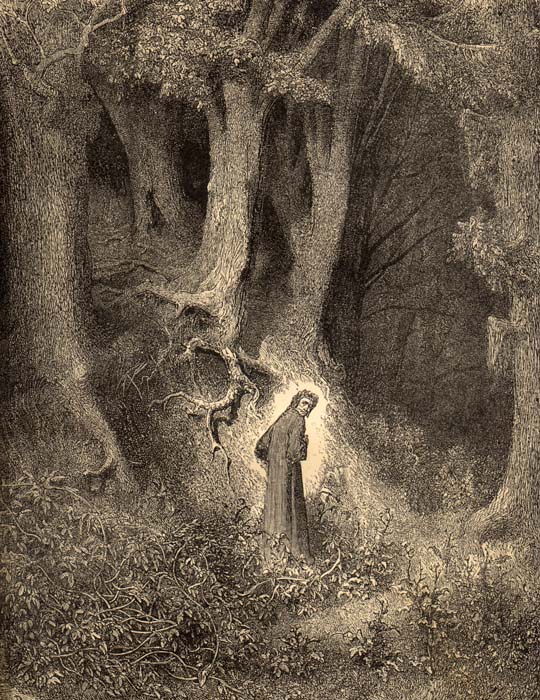

Burton’s long book concludes with some reflections on despair. It is legitimate to wonder whether Burton’s melancholy has its roots in his religious doubts. Despair, this sickness, this murderer of the soul , is agravated when there is a disposition to melancholy , as the power of imagination becomes a curse when conscience is turmented by some sins induced by de devil who, after making us believe that they were something light, now produces an exaggerated remorse. The symptoms are terrible, sadness, fear, anger … a summary of hell. When speaking of the tendency for sinning, Burton switches to the first person, as if he really was making a bitter confession: “I persevere in sin, and to return to my lusts as a dog to his vomit, or a swine to the mire […] I daily and hourly offend in thought, word, and deed”. He accuses himself of faith doubts , not believing in God and just pretending to meet what is expected from him.

Where is comfort to be found? The mercy of God that, like a mother that tenderly takes care of her sick and weak child, instead of rejecting it or punishing him. [Christian’s have always pictured God as a masculine figure, a father, it is nice that here Burton thinks of a feminine figure, a mother.]

Be not solitary, be not idle.

Unhappy, hope, happy be cautious

Sperate miseri, cavete felices